Maryam Akmal

Center for Global Development

Blog

High-stakes national assessments in developing countries tend to have important consequences for test takers. These assessments can determine a child’s future opportunities by deciding whether a child progresses to a higher grade or achieves a certain certification to enter the workforce. Because these assessments are important for both children and teachers, they have a strong influence on what actually happens inside the classroom, and as a result, on the learning outcomes of children.

A recent RISE working paper by Newman Burdett reviews high-stakes examination instruments in primary and secondary schools in select developing countries: Uganda, Nigeria, India, and Pakistan. The paper looks at the extent to which higher-order skills that go beyond memorization and recall of facts are required to excel in examinations. The extent to which assessments are measuring higher-order skills is only one aspect of measuring real learning outcomes, but an important one.

Based on benchmarks from international assessments, assessment questions can generally be classified into the following:

|

Level 1 – Recall |

Recall a fact or piece of knowledge |

|

Level 2 – Apply |

Understand the knowledge and apply it |

| Level 3 – Reasoning |

Critically analyze and evaluate facts and potentially put those pieces of knowledge together in novel ways |

Higher-order skills are important for preparing students for the outside world, by allowing them to adapt the knowledge learnt in schools to different contexts. If students are unable to understand, apply, and use their knowledge in new situations, it is unlikely that what they learn in school would be useful beyond the assessments. Furthermore, higher-order skills are necessary to be competitive in a labor market that increasingly requires skills beyond basic literacy and numeracy.

A geography question from a Pakistani assessment asking students how many fisheries were active in the province of Balochistan in 1947 is a low-order skill question with questionable educational merit. Scoring high on this question requires simple recall. Similarly, a science question asking which part of the cell was discovered in 1831 by Robert Brown is of similarly low educational value. A statistics exam question asking students to write a “brief history of statistics” makes one wonder what exactly is being tested and why.

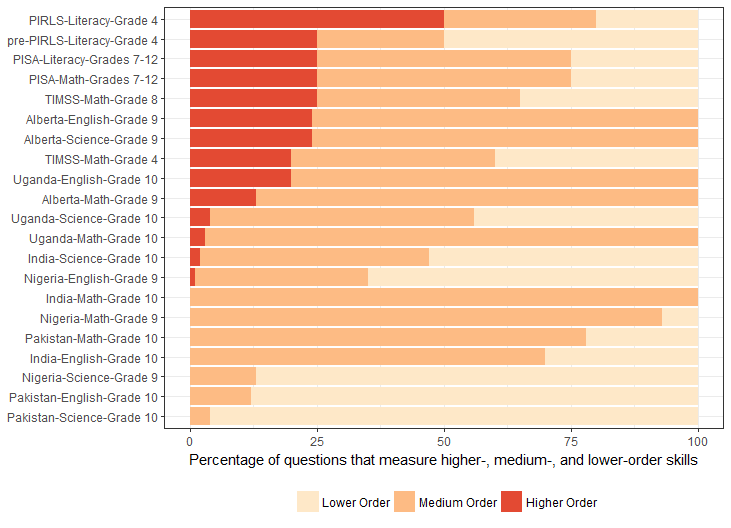

Figure 1. Tests Across the World Measure Higher-, Medium-, and Lower-Order Skills to Varying Degrees

Overall the results from Newman Burdett’s RISE working paper reveal that there is a very small proportion of questions measuring higher-order skills in assessments from developing countries. In India, Pakistan, and Nigeria, higher-order skill questions are entirely lacking except for a small proportion of questions in Nigeria’s English and India’s science assessments. The emphasis largely seems to be on recall of rote learnt knowledge.

On the other hand, internationally benchmarked tests such as PISA, PIRLS, and TIMSS have a heavier focus on measuring higher-orders skills. In fact, international assessments aimed at primary school students tend to have a much higher proportion of questions measuring higher-order skills than national assessments for older students in secondary school in developing countries. For example, TIMSS math test for grade 4 measures a greater proportion of higher-order skills than math tests for grades 9-10 in India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Uganda. Clearly there is a disconnect between what is assessed in these national high-stakes assessments in developing countries and what indicates better learning in international benchmark assessments. Therefore, it is entirely possible to score high on an Indian or Nigerian national assessment and fail completely in PISA or TIMSS. Conversely, a student from the United States could score high on PISA or TIMSS but fail the Indian or Nigerian assessment.

The recent ASER assessment of the skills of Indian youth (aged 14-18 years) reveals how high-stakes but low-order skills assessments bias learning towards simple memorization and do not produce real understanding. They probed simple life skills like telling time. If a clock showed a certain hour (for example, 3 p.m., 6 p.m., etc.), then 83 percent of youth could tell the time. But if the hands on the clock required understanding hours and minutes (for example, 5:45 p.m., 3:20 a.m., etc.), less than 60 percent of youth could tell time. If the test takers were told that someone went to sleep at 9:30 p.m. and slept until 6:30 a.m., and then were asked how many hours that person slept, less than 40 percent could get the right answer—even though over 80 percent of youth have completed grade 8 or higher. So most youth cannot actually use time even if they can tell time.

When the state of Himachal Pradesh did participate in PISA in 2009, it was found that only 2.1 percent of students were above level 2 in reading—which is considered as the “baseline” level of literacy. There were only 5 in a thousand kids (0.5 percent) in India at the levels of science proficiency that require higher-order skills (levels 4, 5, or 6) versus over 40 percent at those levels in a high performing country like Korea.

It is evident that better assessments require improvements to testing materials. Examination boards could benefit from more capacity building in writing questions that test higher-order skills accurately. Review of assessment practices against best practices along with a cycle of continuous improvement could help improve these assessments. However, at the end of the day, assessments and teaching go hand in hand. Any changes in assessments will need to be mirrored in changes to curriculum, pedagogy, and textbooks. One of the key aims of RISE is to take such a systems approach towards making assessments more coherent around learning. While such a system reform will be complicated, it is necessary to ensure that assessments are able to identify real learning and encourage good teaching.

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.