Blog

Understanding the Meaning of Equity Within Education Systems

“Quality Learning for All” and its Relation with Equity in Education Systems

UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4) to “Ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning” raises many questions on both conceptual and practical grounds. Perhaps, one of the most important would be which indicator to use to measure progress in accomplishing it. In other words, how to go from measuring enrolment to measuring quality learning for all (Luis Crouch offered a comprehensive answer in a previous RISE blog post). Another main question would be to understand what does “for all” entail. This leads us to think about equitable growth in learning outcomes. Quality education should reach the whole student population of a given country, irrespective of variables such as gender, race, and socio-economic background.

RISE recently held a panel discussion “Equal Rights and Equal Rise: Contextualising Equity in Education Systems” in which Caine Rolleston and Luis Crouch (both members of the RISE Intellectual Leadership Team) presented the latest RISE Insight Note “Raising the Floor on Learning Levels: Equitable Improvement Starts with the Tail.” The discussion focused on how to understand equity problems in education systems. Angela Little (UCL) and Pauline Rose (REAL Centre, RISE Ethiopia Country Research Team) offered in-depth comments and raised more questions about the implications of equity within education systems.

Rolleston characterised the current learning crisis as also an equity crisis, since in many countries the large majority of pupils are excluded from receiving quality education. Taking Rawlsian concepts such as the principle of difference (which roughly means that inequalities can only be accepted when they benefit the worst off in a given society), Rolleston defined inequity as an unfair inequality (one that does not benefit the least advantaged). Therefore, equity is related to fairness or justice and while some inequalities may be desirable or fair (for example recognizing merit though scholarships), inequity will always be undesirable in an education system because it won’t provide an effective equal chance to access the wide-ranging benefits of education.

Sources of Inequality that Lead to Unequitable Outcomes

Crouch, using data from SACMEQ and PISA 2015, pointed out that “pure inequality” or total aggregated inequality in learning outcomes (the difference in scores between students at the 75th and 25th percentile) is extensive in developing countries, and surpasses comparisons by gender, wealth, and location, which only partially explains low learning levels.

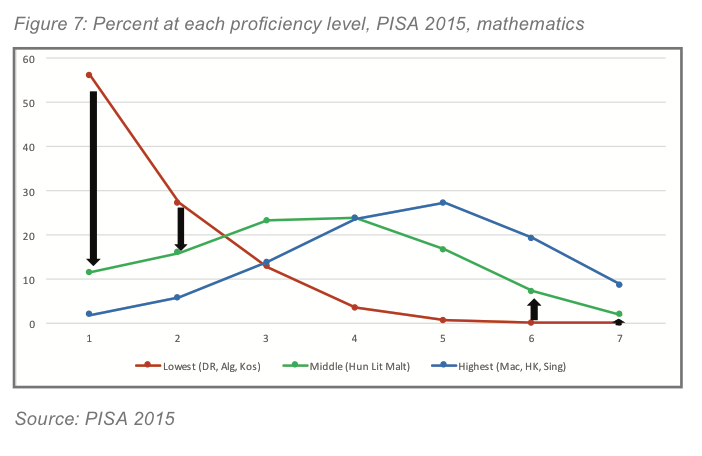

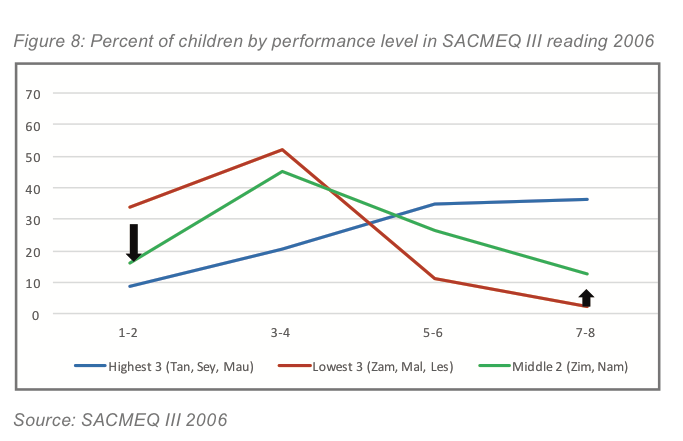

Additionally, by using an infographic with figures from TIMSS 2015 and graphs constructed with cross-sectional data from SAQMEQ II and PISA 2015 (see Figures 7 and 8, included in the Insight Note), he explained that countries at the bottom of rankings may consider improving learning outcomes by implementing a two-step strategy. First, focus on strategies to reduce the proportion of children with very low performance and second, improve from a middle to high ranking status through policies that facilitate increasing the proportion of children with high performance.

Policy Implications in Global Education

Rolleston and Crouch found that countries need to focus on “pure” and unjust inequality caused by “quality lotteries” that affect poor students disproportionally in comparison to the rich. Lack of standards and quality control should also be tackled to reduce inequitable learning outcomes.

Crouch also argued that, within this framework, the role of international agencies would be to help countries to improve their average learning outcomes by focusing on the students at the bottom (the cognitive ultra-poor).

Just the Tip of the Iceberg: Equity Within Education Systems as a Roadmap

Angela Little applauded Rolleston and Crouch’s clear conceptual distinction between inequity and inequality. She also raised questions on what policies caused the high performers in PISA and SAQMEQ to achieve those results over time and disputed whether there was a “long tail” of low learners or a “bulge” of low learners.

Pauline Rose, who commended the fact that RISE and the authors have highlighted the issue of equity, brought the topic back to education systems research. If education systems need to be coherent and aligned towards learning, then it follows that they need to be also aligned towards equitable learning. She also noted, that the data used excludes children who were not assessed (due to the nature of PISA and SAQMEQ) and that initiatives such as “PISA for development” should continue to be pursued to have more information about learning outcomes in middle and low income countries.

Equality and equity in the provision of education are topics that should be central for governments and international organisations. In that sense, the wording of SDG 4 is beneficial to advocate for equitable growth in learning outcomes in both developed and developing countries.

How can an equitable education system be achieved? What policies would support it? These are some of the questions that are at the core of the RISE Programme; raising learning outcomes won’t be possible if the needs of students at the bottom are not included in policymaking and research.

Author bios:

RISE blog posts and podcasts reflect the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the organisation or our funders.